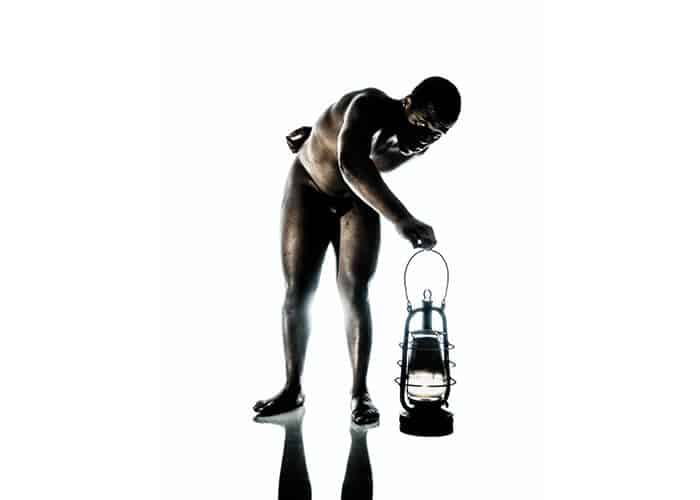

Mishkaah Amien, Beyond the Visible, 2015. Paper, 56 x 67 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

“How can one be Persian?” Montesquieu wrote in his Persian Letters in 1712, ironically on the subject of European ethnocentrism. Centuries later, the question has become: “How can one be Arab?”

In conventional perceptions of what it is to be ‘Arab,’ we find commonplace indicators of what ‘Arabism’ is, such as the lifestyle and traditions, religion, the desert, family, women, the veil and fundamentalism. Used in their essentialist sense, these ‘criteria’ are rather reductive and contain as many questions as they do misunder-standings.

As a result of these misunderstandings, there is topical and persistent confusion that consistently assimilates the image of the ‘Arab’ and the ‘Muslim.’ This amalgam – that marks the representation of the Arab world in the Occident – often refers to a homogenous block that is unchanging and prey to fanatical passions. More than that, on the international art scene, this amalgam sometimes extends to Muslim countries in general. Exhibitions that are placed under the label of MENA (Middle East and North Africa) may include Iranian and Turkish artists who do not speak Arabic, nor belong to this language group, however, in the exhibitions of African art, ‘Arab’ artists are included (Egyptian, Algerian, Tunisian, Moroccan) who are simultaneously ‘African’ in identity.

If the link between all the groups that constitute ‘the Arab world’ is that of language, a shared history and a common civilisation, this linguistic heritage and cultural history does not exclude diversity. ‘Arab identity’ or ‘Arabism’ (as they say ‘Europeanism’ for Europe) is constituted by different elements that are combined to construct a complex identity. From this point of view, belonging to this identity is not uniform. Rather, it is plural because there are other affiliations that take an important place for some within this identity, such as the Amazigh in North Africa, or the Kurdish people who are spread across numerous Arab countries. Kurds are Iraqi, Syrian or Turkish, but above all they are Kurds, therefore, they belong to another sphere of identity. The unifying function of the Arabic language must be qualified as literary Arabic, which is not the mother tongue of most people or even the language used in daily life by all Arab countries, particularly in North Africa where one is more likely to hear Maghrebi (in Morocco) and Tamazight (in Algeria). The ‘Arab world’ is composed of multiple communities and it would be reductive to approach it as a monolithic assembly overwhelmed by Islamic fundamentalism.

In the same way, the term ‘Arab’ cannot only be understood in relation to notions of territory and boundaries because living in an Arab country cannot be a kind of guarantee for such membership in view of the turmoil and ongoing mobility of populations with regards to globalisation.

Slimane Rais, Koul chi yefna (Everything will disappear), 2015. Performance installation. Image courtesy of the artist.

A nomadic identity is visible today which operates as much on the ‘outside’ as on the ‘inside’ of countries where accelerated urbanisation has revealed sub-identities. Human mobility (migration, displacement, population movements, diasporas) has ensured that these identities have become multiple, hybrid and organised into diverse territories.

Rather than speaking of geographic territories, one could speak of ‘identity territories’ that are symbolic places, like Mecca and Medina, Palestine, historic sites such as cities like Cairo, Damascus and Jerusalem, but also separate territories in Europe or elsewhere such as Marseille, London or small neighbourhoods in major cities of the world. All of this contributes to the ongoing construction of an identity in constant transformation. An example of this is provided by the artists included in the exhibition ‘Arab Territories,’ held at the Palais de la culture Mohamed Laïd Al-Khalifa in Constantine, Algeria. They are Arab-Iraqi living in Rome or Iraqi-Kurd living in London; Algerian, Moroccan and Tunisian living between France and their country of origin, Palestinian-Iraqi living in the USA, Lebanese living between France, Lebanon and so on.

Today more than ever, in view of recent history, borders crossing the Arab world are topical. They take forms other than the solely territorial and require new readings of its mapping. The borders are legal, subject to the territorial imbalances, as well as influenced by socio-economic disparities, with differentiated policies or complex dualities (Maghreb/ Mashreq). Everyday the news shows the territory in its territorial dimension, battered by wars and conflicts, the political, economic or cultural uprisings in one country affecting its neighbours due to strong historical affiliations.

Youssef Ouchra, Peace cure, installation photo, 2015. 500cm x 91cm, various material. Image courtesy of the artist.

Recent developments in these countries have shown that the land issue has become a repository of identity and an exercise for the right to public space. Thus the occupation, appropriation or re-appropriation of spaces becomes a major issue for change because it represents the image of the human relationship to living space. We can see that this issue is at the heart of the news and the subject of various claims in several countries.

When artists approach the subject of territory, they make a complex approach in order to refine our understanding of major contemporary problems. As a result, most of the proposed works in the exhibition ‘Arab Territories’ are very close to the news. Art invites us to think territorially, economically and politically, and pushes us to ask questions in order to get answers. By inviting reflection, art not only provides a complex and subjective message, but also a critical eye.

What perspective does art from the Arab World provide for these territories? Given the geographical and linguistic variety of these different paths and stories, which images are proposed? What links exist between the geographical boundaries and the artistic realm? What trajectories, affiliations and lives are sketched by the imagination? In addressing these pressing questions, ‘Arab Territories’ demonstrates how artists today, in different places and styles, continue to nurture their works with a living sense of the ‘Arab world,’ highlighting the boundaries of a moving map, supporting – in many ways – the issues of territorial representation.

Nadira Laggoune is a curator and art critic who lives and works in Algiers. Her primary focus is on giving visibility to new generations that are emerging in the field of contemporary art in Algeria and the Maghreb. She recently curated the exhibition ‘Arab Territories’ as part of the programme for Constantine – capital of Arab Culture 2015 that ran from 7 November – 31 December 2015 at the Palais de la culture Mohamed Laïd Al-Khalifa in Constantine, Algeria.